There’s an old business axiom we all know that goes like this: The customer is always right.

In this digital economy, it turns out that axiom has to change to read: The customer’s data is always right.

Let me illustrate with a little story.

I recently decided to buy a new car and trade in my old one. I’d had the old one for about six years and I drove it about three-thousand miles a year. I know that sounds crazy but it’s true. I drove it once out of state to Ohio to see family. That’s it. Otherwise it stayed within a thirty mile radius of home. I like to joke that I am that little old lady that only drives her car to church on Sunday.

So imagine my surprise when the car dealer informs me that my odometer reading is inaccurate – off by more than 30k – based on a single line of data held within the vehicle history report accessed by the dealer. A line of data that further claimed my car had been serviced in North Dakota two years prior.

This discrepancy is not to be taken lightly. Odometer readings inform trade in value and it’s illegal to tamper with them (fines and prison are possible). Given that the actual odometer read a much lower number than the one in the report, well, you can imagine the dealer was a bit unsettled. He was faced with the undesirable decision to trust me – who insisted I have never taken the car to North Dakota – or the data that claimed I did?

The question quickly boiled down to “is the customer always right” or “is the customer’s data always right”?

It turns out this isn’t the first time someone’s been bitten by inaccurate data in a vehicle history report. Most of the data is still manually entered, so mistakes happen. But the process of correcting those errors requires that the person who entered it admit to making a mistake. Which means they have to remember they made a mistake some five, ten, or even fifteen years ago. If the technician that entered the data is even around to admit the mistake.

In the end, I left with my new car and the dealer was left to handle correcting the report. I’m willing to bet many of you have a similar story. It’s all too common when you’re operating in a digital economy.

The Human (Error) Factor

As we continue to expand our reliance on machines for solving problems, mining data, and making decisions, we need to be aware that the data we have may not be accurate. At some point in the custody chain of that data there was a human being involved. And an axiomatic truth of being human is that we make mistakes. A single wrong keystroke by a service technician in North Dakota six years ago and suddenly you’re under hot lights and being interrogated about every car trip you’ve ever taken.

We need to be careful about how much faith we put in the data we use to make decisions. It isn’t just accidental errors we need to be worried about, it’s intentional errors as well. Your data, I guarantee, is dirty.

The design of DNS is pretty amazing in its designation of authoritative sources versus non-authoritative. Because you know that if there’s a discrepancy you can go to the one, true source and find the truth. With customer data, there’s no such thing. That’s a potential red flag because the systems we use now – and will be using in the near future – can’t necessarily know what’s accurate and what’s not. After all, there’s no place to verify its veracity. No certificate authority, no designated authoritative sources like DNS. And in many cases, no way to dispute the data.

As we continue to build digital images of our customers out of bits and pieces of data, we need to be cognizant of how impactful that data can be – both on us, as business decision makers, and on customers, as human beings who have to live with the consequences of whatever conclusion is reached based on that data.

As providers of application security solutions, we often beat the drum of data and identity protection from exfiltration; from theft. But we don’t often turn the equation around and talk about the very real possibility of data corruption, either accidentally or vindictively.

We should – before it becomes a trending topic on Twitter.

We’ve seen the rise of retributive digital strikes on people in many forms. Because 911 dispatchers can’t get accurate locations and addresses from cell phones, victims have suffered deadly swatting incidents. Revenge porn is a thing and impersonation of our friends and family on social media happens all the time. And it’s been more than 3 years since Kustodian CEO Chris Rock demonstrated how fraudsters could artificially ‘kill’ someone for a profit or prank due to vulnerabilities in most countries’ death registration processes at DEF CON (CS Monitor). For those paying attention, that was one of the hacks used in the 1995 film, Hackers, along with cancelling someone’s credit card and submitting false personal ads as retribution for some slight – perceived or real.

It’s only a matter of time before such vindictive behavior spreads to dirtying up data elsewhere.

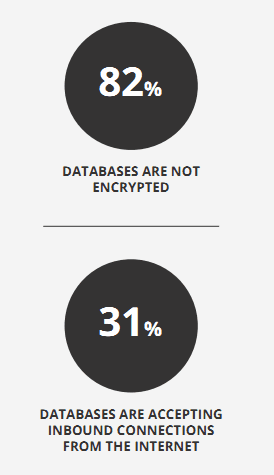

If you think I’m suffering from a tin-foil hat on my head, remember the RedLock CSI report from 2017 that noted 31% of databases had a port open to the Internet. To anyone. Remember the MongoDB debacle, where more than 27000 databases were open to public access. The wrong person with the right database left open can wreak havoc on your data.

That’s a problem because we have reached the inflection point where data is often treated as an inviolate and infallible version of the truth. Thanks to a data entry error that ‘truth’ could have landed me in prison.

Digital Data Diligence

As we continue to expand how much of our businesses – and lives – are stored in the digital realm, we should take a deep breath and remember that the bits and bytes in our data warehouses represent some aspect of real human beings. The diligence with which we treat that data reflects our attitude toward that real human being that is our customer. Especially when we can’t know what tidbit of data we’re entering today might be interpreted in a way that harms the customer later. After all, the entry my vehicle history record was simply to register an oil change in North Dakota. There was no malice intended, but the result could have been disastrous for me.

Whether it’s crafting security policies with an eye toward preventing data corruption, controlling access to apps and databases, or greater attention to manual entry of data, we need to remember that while the data doesn’t lie – it represents exactly what the person entered – the person who entered it might have.

About the Author

Related Blog Posts

Why sub-optimal application delivery architecture costs more than you think

Discover the hidden performance, security, and operational costs of sub‑optimal application delivery—and how modern architectures address them.

Keyfactor + F5: Integrating digital trust in the F5 platform

By integrating digital trust solutions into F5 ADSP, Keyfactor and F5 redefine how organizations protect and deliver digital services at enterprise scale.

Architecting for AI: Secure, scalable, multicloud

Operationalize AI-era multicloud with F5 and Equinix. Explore scalable solutions for secure data flows, uniform policies, and governance across dynamic cloud environments.

Nutanix and F5 expand successful partnership to Kubernetes

Nutanix and F5 have a shared vision of simplifying IT management. The two are joining forces for a Kubernetes service that is backed by F5 NGINX Plus.

AppViewX + F5: Automating and orchestrating app delivery

As an F5 ADSP Select partner, AppViewX works with F5 to deliver a centralized orchestration solution to manage app services across distributed environments.

F5 NGINX Gateway Fabric is a certified solution for Red Hat OpenShift

F5 collaborates with Red Hat to deliver a solution that combines the high-performance app delivery of F5 NGINX with Red Hat OpenShift’s enterprise Kubernetes capabilities.